Life on the islands of Åland: a special place for autonomy, pacifism and cooperation. A territorial entity lying between Finland and Sweden and taken as model for the resolution of ethnic conflicts in Europe

Some years ago I visited the Åland Islands (pronounced: Oland; Ahvenanmaa is the name in Finnish), a small archipelago located in the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Finland.

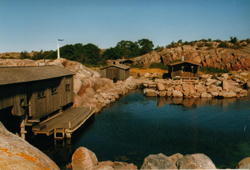

The summer was very bright, as often happens so far north. Magnificent views of the islands of Kökar, or the smaller Källskär, across whose peaceful horizons the Swedish-speaking Finnish author Tove Jannson wrote some of her books.

But in addition to the landscapes, I was impressed to discover that the identity of Åland’s inhabitants also comes through the realities on the islands, its autonomy, peace and disarmament.

The name of Åland had appeared as an example for a political solution in the negotiations (but then blocked) on the status of Kosovo, but also for the separatist republics within both Georgia (Abkhazia and South Ossetia) and Azerbaijan (Nagorno-Karabakh). This is not the first time that the archipelago has been proposed as a model for solving inter-ethnic conflicts, or those between a majority and a minority within the same territory.

It is obvious that the conflicts that have broken out in recent years in Europe, especially those related to ethnicity, are extremely difficult to solve and present very complex issues. It is also true that the population of Åland is small: just 26,000 people, virtually all Swedish-speaking. Of these, 11,000 live in Mariehamn, the capital, with another 13,000 in the countryside and a further 2,000 on the islands. A mere 80 out of the 6,429 islands and islets that make up the archipelago are inhabited.

The example of Åland has, however, become a reference point for the provision of conditions that safeguard the cultural and linguistic rights of a homogeneous minority within the sovereignty of a state with a different majority.

The islands lie at the centre of a small Euroregion which also includes other coastal archipelagos belonging to Sweden and Finland.

A bit of history

Belonging to the Kingdom of Sweden until the Napoleonic Wars of 1808-1809 when it passed to Russia, the Åland islands were integrated into the Grand Duchy of Finland, which at the time enjoyed a semi-autonomous status within the Czarist Empire. For the Russians they represented an important strategic bulwark in the Baltic and were manned as a outpost during the Crimean War. Following the Treaty of Paris (1856) the islands were subject to demilitarisation.

In December 1917, after the October Revolution, Finland became independent. For obvious political, linguistic and cultural reasons the islanders wished to opt for reunification with Sweden. Instead, they only wrested the status of autonomy from the Finnish Parliament in 1920, a status they considered inadeguate.

The issue was settled in 1921 by the newly-formed League of Nations (the forerunner of the United Nations, the UN), whose Council decided in favour of a Finnish Åland. The islands, however, were granted very broad autonomy which guaranteed language rights and confirmed the area’s demilitarisation and neutrality. As a result of the Autonomy Act (1922), revised twice (in 1951 and 1993), Åland enjoys one of the highest degrees of self-governance in Europe.

Autonomy

The Parliament, opened in 1978, is actually a small three-storey building in the capital Mariehamn. There sit the 40 members and visiting it you appreciate the almost family atmosphere that surrounds it. Stripped of any formalities and wearing a simple blue shirt, Roger Nordlund, now President of the Parliament and, at the time of my visit, Vice-President of the Government of Islands (the Landskapsstyrelse), said: “Finland handles foreign policy, criminal law, the courts, currency and a part of taxation, while we administer the share that goes to local communities. The Lagting, the Åland Parliament has jurisdiction over everything else. The archipelago also has a fixed representative in the Finnish Parliament and the name ‘Åland’ also appears on the (Finnish) passports of its inhabitants. The Act stipulates that the only official language is Swedish, although in the courts citizens can also submit their applications in Finnish.

The economy of the islands, which in 1954 got its own flag and has been issuing its own stamps since 1984, is based on the shipbuilding industry, trade and tourism. “Forestry is more important for Finland” adds Nordlund.

On 1st July 1999 a directive of the European Union (EU) came into force which saw the disappearance of duty-free areas, where it had been possible to buy all sorts of goods without paying VAT. One of the few exceptions to the ruling is Åland”.

The giant ferries of the ‘Vikingâ’ and ‘Silja’ shipping companies connecting Finland and Sweden, as well as the smallest company, ‘Eckerö’, are registered in Mariehamn. Traffic through Åland involving the enormous ships has greatly increased in recent years, from Stockholm to Turku, but also connecting the Swedish capital and Helsinki. Tallinn in Estonia is also now on the routes.

Ticket prices are low because most of the revenue, about 75%, comes from duty-free purchases on the ships. The focus is on alcohol which is expensive on the mainland. An overnight journey on one of these ferries, which in fact are genuine cruise ships with bars, clubs, discos, and saunas, only confirms the Nordic reputation as hardened drinkers, especially weekends which witness scenes that hardly bear description.

“To preserve this condition a special protocol was signed with the EU, which cannot be modified by Brussels directives, so that the duty-free status remains in force even after 1999. It was too important to our economy. The Åland islands have thus acquired the status of a ‘special territory’ which remains excluded from the harmonisation of taxation rules. They have been able to maintain the duty-free, creating a de facto customs barrier to union with the rest of the EU that puts producers in the archipelago at a disadvantage. Clearly, however, the move seems worth it, a fact confirmed by referendum in which 74% of the islanders were in favour of entry into the EU.

“In the future I think we will depend increasingly on tourism, focusing mainly on quality“, continues Nordlund. “As in other Nordic countries, the flagship of Åland is the natural environment, especially for cycling, fishing or camping, but the tourist season is very short and confined to the summer months. For the rest of the year the ferries are still needed, with a ‘short stop-off’ in the islands allowing them to retain their duty-free status.”

On Åland, if the truth be told, ties with Finland are not so strong. Knowing only Finnish it would be impossible to get by, although in Helsinki there is bilingualism and although elsewhere in the country Swedish is the second official language, only 6% of the 5 million Finns have Swedish as their mother tongue. “We know we are Finnish citizens, but we are very close to Sweden, as far as linguistic and cultural issues are concerned. People here watch Swedish TV and read Swedish newspapers. In general relations with Finland are good, although on some occasions we have differing opinions, but this is a perfectly normal struggle between the centre and the periphery. With regard to monetary union, there is no advantage for us as long as Sweden remain outside the Euro-zone as an important slice of our trade is done with them.” The inhabitants of Åland therefore look more towards Stockholm, although there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that the current state of affairs represents the best option for them.

A substantial part of the taxes levied is spent on education, and to ensure that schools and shops survive even on the smaller islands which are at risk of total depopulation. In addition, one third of the islands students continue their education in Finland, the rest go to Sweden. Most return home after completing their studies, but many stay away. “In the 1950’s everyone who left emigrated to Sweden. Some of their children, who came here on vacation in the summer, have decided to return.” stresses Nordlund.

Given all the peculiarities of the archipelago, the law on residence is very strict. “I have lost my rights to live on Åland, although I was born there and still own my father’s house there.” confesses Erland Eklund, professor at the Swedish University of Social Sciences in Helsinki, “This happens if you live away from the islands for more than five years, as was the case with me.

Identity

In 1921 the demilitarization of Åland took place. No installations, activities or military personnel may be stationed on its territory, even exercises are not permitted, and the Finnish navy cannot enter the territorial waters around the islands. In addition, for many years young islanders have been exempt from military service if they have been resident on the islands since the age of 12.

After ten years of discussions on how to tackle the study of peace from both a theoretical and practical perspective, the ‘Ålands Fredsinstitut’ – the Åland Islands Peace Institute – was created in 1992.

The identity of the inhabitants of the archipelago, stimulated by the various peculiarities and helped by their own symbols, has strengthened over time. Today almost all the islanders consider themselves as simply inhabitants of Åland rather than Finnish or Swedish. “The local identity passes ever more frequently through aspects such as autonomy and neutrality” explains Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark, Director of the Institute, speaking on the phone to me. With a Greek father and Swedish mother, she is an expert in international law.

“There is a certain pride in belonging to a demilitarised region” she continues. “You can see this from the way tourist attractions such as the fortress of Bomarsund, the Russian base built in 1852 and destroyed by the British and the French in the Crimean War, are presented, emphasising that this was the last conflict fought on the islands.”

The example of Åland for the resolution of conflicts should be set against the context in which its current status arose. “At the time of the Crimean War it was not easy, but all parties involved were open to compromise. Even in modern conflicts, an agreement can only be reached with this precondition.”

The Institute is working on EU projects that promote Baltic cooperation, carrying out studies. These are often comparative and related to the archipelago’s peculiarities such as demilitarisation, cooperation on security at European level, the rights and participation of minorities, autonomy – studies that it then publishes. It has also created a network of non-governmental organisations in the Baltic region, mostly in Lithuania, Belarus and the Russian territory of Kaliningrad, especially catering for young people and women in difficulty.

One of the current internal challenges involves immigration. “Until now the islands have remained ethnically homogeneous, but new inputs to the system are required. The average age of the population is rising and there is a need for young people, including foreigners, to come and live here, but decisions involving immigration are not in the hands of the local autonomous Parliament but are made by the Finnish state. Here as well there is a need for mediation.”

The population does not know the legal details and conditions of the islands autonomy but realises their uniqueness. “The system foresees “motors” that will always keep open the possibility of negotiations and discussions. The Governor is a representative of the Finnish state, but appointed on the advice of the President of the Parliament of Åland and there is also a joint delegation consisting of representatives of the two parties. The third level comes through the adherence to EU legislation.” concludes the director. “The limits of autonomy are therefore continually re-negotiated, and this is one of the keys to the success of Åland.” x

Author of this story: Alessandro Gori

Alessandro Gori (born in Udine, Italy in 1970) as an independent journalist has published photos and articles in ten different languages in daily newspapers and magazines in 15 countries on a wide range of themes. He specialises in the Balkans, the former Soviet Union, Northern Europe and Latin America.